Location of Hatay in Turkey

Tell Atchana, the Excavation Site

Layout of the Palace at Alalakh

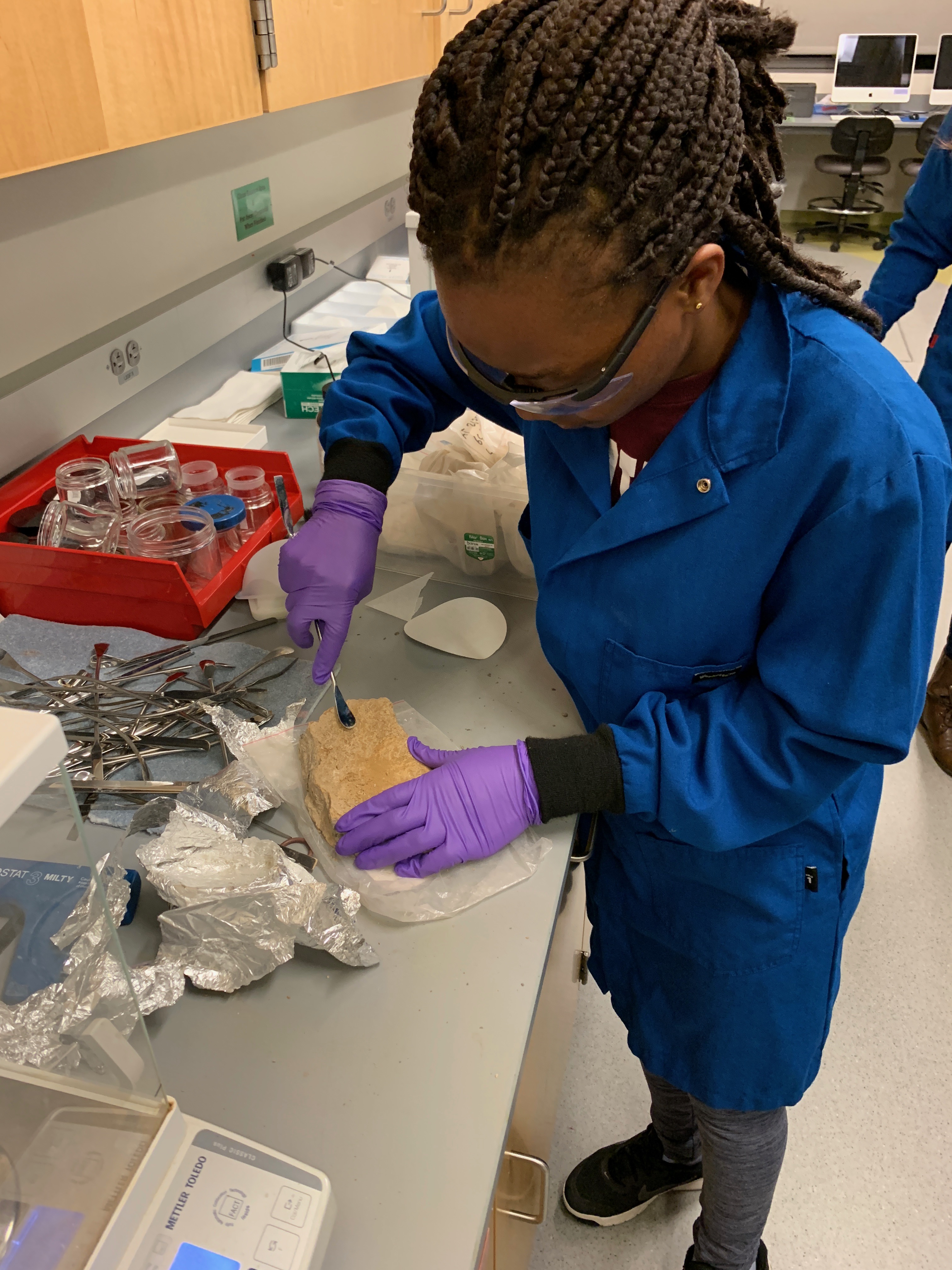

In the process of trace analysis, artifacts are treated with compounds such as dichloromethane and methanol in order to dissolve the organic molecules that may exist. Following this, the solution is run through a mass spectrometer, in order to determine what the artifact may have contained.

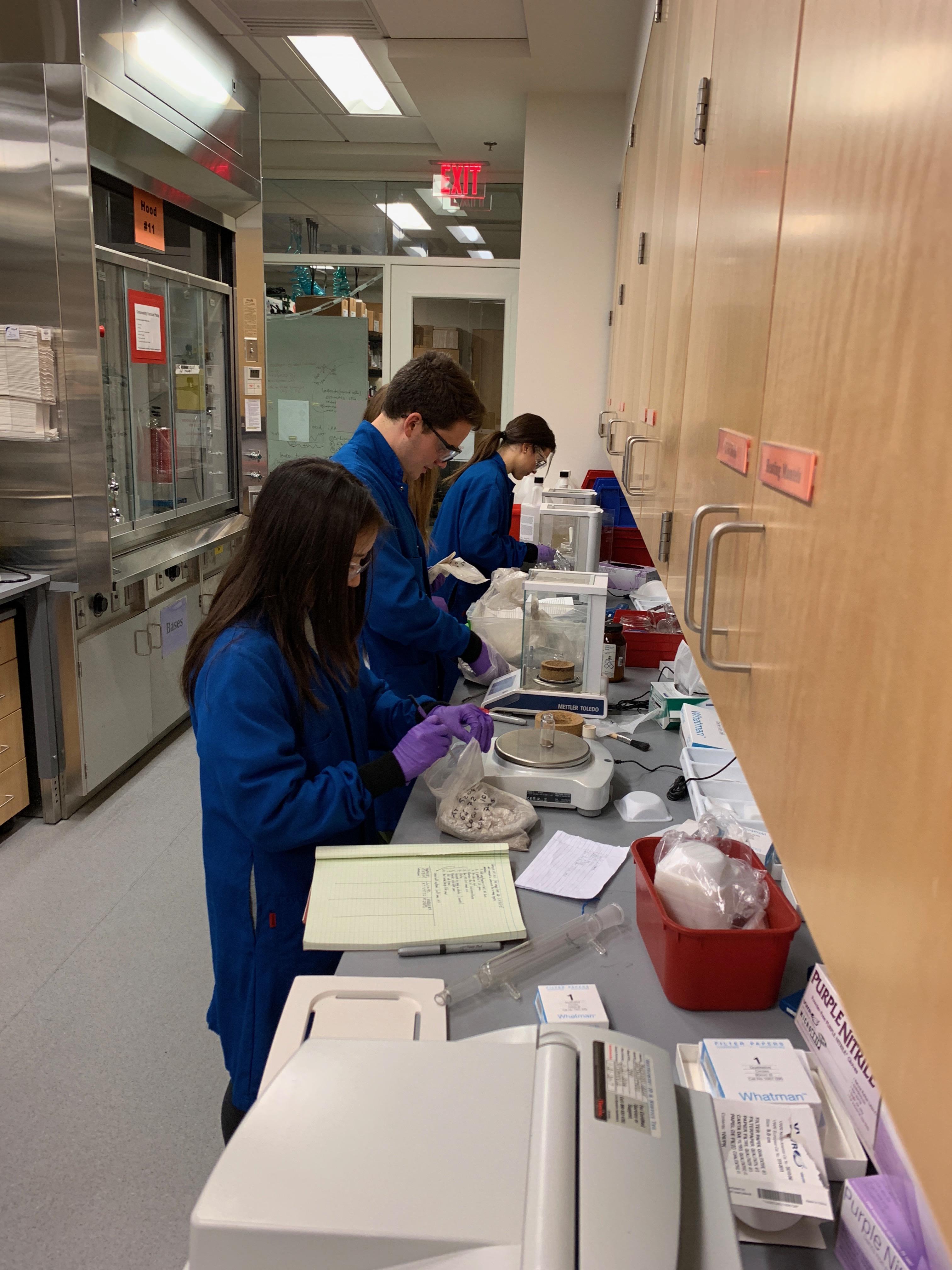

Students played an integral role in the process, running tests and taking data that would be sent back to the archaeological site in Turkey.

The particular artifacts studied by the Harvard team came from a palace in Alalakh. Given the expense and status of wine in the Late Bronze Age, the team was hopeful they could find traces of alcohol. Over the course of this project, the trace analysis students got to apply their background knowledge from Ancient Lives, and in turn learned more about ancient history. Davis states, “I learned a lot more about the scientific reality of archaeology. The results we get in a textbook are very sanitized. In a textbook you see the wine. Results are less clear. You have to piece together different ambiguous pieces of evidence so you can put together a cohesive narrative that can end up in a history textbook or a paper.”